Slow Processes

Apr 12, 2022

It’s a risky thing, as an emerging artist, to choose to create artworks that are slow to make and/or evolve. In a way, it feels like a deliberate act of defiance against the fast-paced risk-reward systems that contemporary society seems to prize. The artist is making a statement about the value of time being more significant than the gratification of the immediate.

An emerging Adelaide artist who I feel responds to the value of time is Kasia Tons (born in 1985). She works by immersing herself within her environment. Immersion takes time. When you immerse yourself in a process or activity, you become absorbed. Your engagement in the process or activity implies commitment. Commitment to something also requires time. Kasia Tons makes art works outside of an interior studio – she makes “the outside” her studio. Travelling within a natural environment that becomes her place of making is important to her creative philosophy.

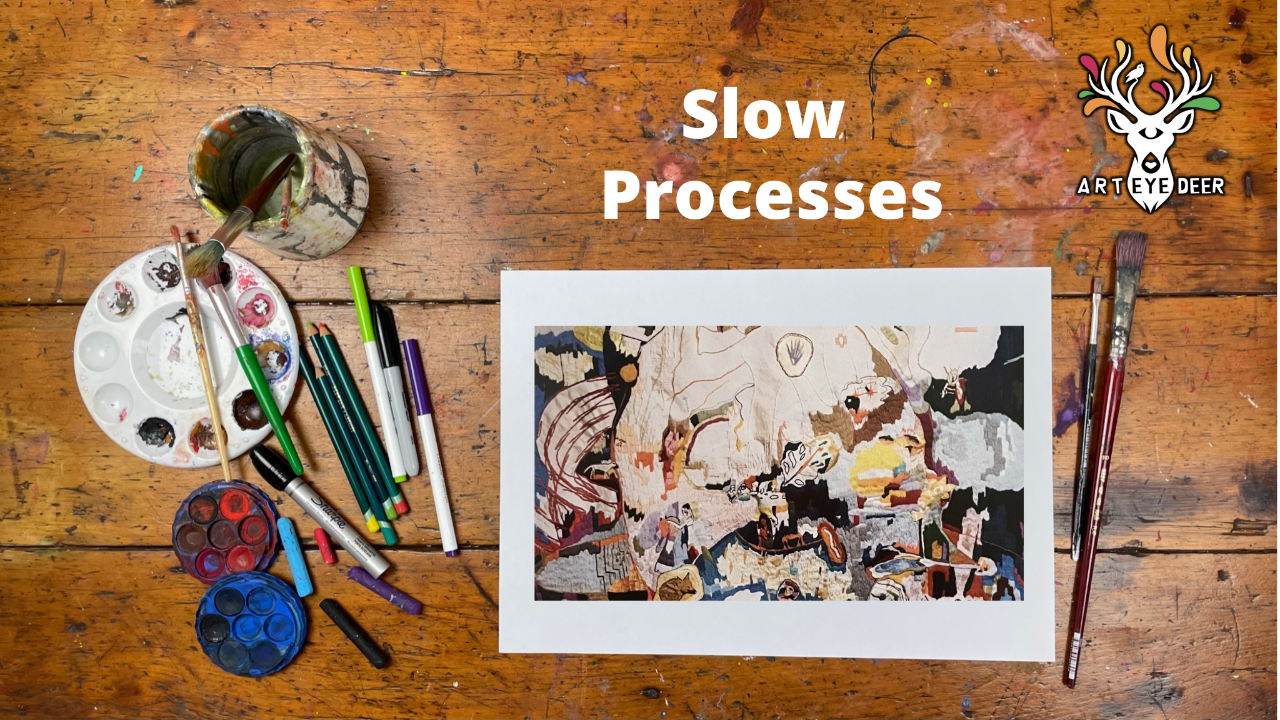

Hand stitching on canvas is one of her modes of expression. The work that I want to discuss is titled After, created in 2020 (a detail of which heads this blog). What’s extraordinary about the slow process of making this stitched work is that it evolved over several months in several locations. I read an article about Tons’ work that discussed the journey of making this work that took place in New Zealand. She physically carried the canvas every day, everywhere in the rugged environment she went, drawing on it during the day and stitching into the drawing when camped at night. The canvas is large and bulky – 171.5cm x 98.0cm. She isolated within the natural world, drawing and stitching as time allowed. Eventually, Tons had to concede to the imposition of a Covid lockdown, going indoors where she then completed this work.

What of the title of this work? How does it fit into Kasia Tons’ slow processes? She was inspired by a 1909 sci-fi novella (a short story) The Machine Stops by novelist E.M. Forster. In this story, our world is ruled by a machine and humans live underground, isolated from nature, socially distanced and restricted in what they could do. Do some of the conditions of this story sound familiar to you, one hundred and thirteen years later? The After of the artwork title addresses lots of things such as: what comes after a scenario like the one Forster describes? Are we placing too much of our time and energy on social media platforms that drain us of our initiative whilst increasing our dependence on “others” who often only exist for us electronically? Do we value technology above face-to-face human interaction? Will there be a future time when we “forget” how to do things manually because of our reliance on machine technology? What happens after the machines stop? How would we survive if we have let go of our capacity to invent and make?

In walking around New Zealand for two months, Kasia Tons sought to offset some of these concerns by giving her senses over to nature. She hiked through a myriad of diverse terrains and climate conditions, each demanding something different of her as a person and an artist. She paid attention to the details of the natural world. She took time to absorb her surroundings. Sometimes she would come across other hikers, but mostly she was alone, except for the companionship of that big, awkward cloth in her backpack. Can you imagine the patina - discolouration, staining and layers of dirt and dust that the cloth collected as she drew on it on the ground with pen, then stitched into marks she made with her collection of threads? The cloth became a memory keeper, a visual diary of her thoughts and experiences. In essence, the cloth was her form of self-expression – one that wasn’t tied to technology or the digital world, but rather, identified her preference for the hand-made. In her wanderings, she identified with past artists and artisans who used their hands to craft their visions. One such artist who championed the relationship between nature and the hand-made was William Morris. Interestingly Morris died just 9 years before Forster’s story was published. I think Morris would have been devastated by a fictional future such as Forster described. Spend a bit of time looking Morris up online – it’s amazing how relevant he still is with artists and craftspeople – they understand that the skills he had are still important for self-expression.

All this is not to say that Tons doesn’t use technology. In fact, her hand-made works sit alongside digital works like animations of her stitched artworks and evocative digital images of her cloths placed in the natural world. The point is, that she is aware of the pressures that screen time in particular, places on us. Screen time sucks away time – have you noticed this? Tons says that when she returned to lockdown after her wanderings, it surprised her how easily she slipped into internet dependency – social media, online chats, video calls, video games, messaging, Instagram posts that documented everything and nothing at the same time – all of which she said left her feeling “a bit empty”.

Screen time is great as a research tool – here I am asking you to research artists’ works. We can find snippets of information from different sites that helps us to create a “picture” of something that we’re researching. In my opinion, that’s worthwhile. So too is screen time for leisure – maintaining a social media profile that acts like a diary of you, or your interests is a contemporary way of introducing yourself to the world. But the “world” isn’t just digital technology. Tons would have you think about a balance between the natural world and the screen. The “After” of the title tells us to get out of the chair, or off the couch, or to step away from a digital device and trust our instincts. What is the best way to do that? Observe nature, interact with it, marvel at it, and above all, protect it. Nature is all about slow, rhythmical and cyclical processes. We can see the beginning and the end, but not at the same time. Nature teaches us about time. Time is what we need to process our thoughts, develop them into ideas, experiment with them, formulate them into something concrete, examine the process and artefact (a thing, product, object, article, item, artwork) revise it if necessary, and finally to present it to the world as a reflection of our unique self-expression. This is what the evolutionary processes of nature have been doing for millennia.

And the bottom line? Slow processes have a very real and necessary place in our world.

Wendy Muir

Art Eye Deer Teacher

Image: Kasia Tons, After, 2020 [Detail]. Cotton and wool thread on canvas.

AGSA Magazine, Issue 43, Winter 2021. Photo: Madisyn Zabel